Removing Freeways - Restoring Cities

Produced by the

Preservation Institute

Introduction:

Tear It Down!

by John Norquist

San Francisco, CA:

Embarcadero Freeway

San Francisco, CA:

Central Freeway

Milwaukee, WI:

Park East Freeway

Toronto, Ontario: Gardiner Expressway

New York, NY:

West Side Highway

Niagara Falls, NY:

Robert Moses Parkway

Paris, France:

Pompidou Expressway

Seoul, South Korea

Cheonggye Freeway

Freeway Removal

Plans and Proposals

Conclusion:

From Induced Demand

to Reduced Demand

by Charles Siegel

Niagara Falls, NY

Robert Moses Parkway

Niagara Falls is thriving. The Casino Niagara is attracting 20,000 tourists a day, new hotels are being built, and business is booming.

But that is in Niagara Falls, Ontario. Things are very different in Niagara Falls, New York, where the population went down by more than 10 percent during the 1990s alone, and where over thirty storefronts are boarded up on Main Street.

New York has established a state agency to revitalize Niagara Falls. To make the city more attractive, the agency has already replaced the four-lane Robert Moses Parkway with a two-lane road and pedestrian and hiking trails. That was not good enough for the Niagara Heritage Alliance and the Sierra Club, who advocated removing the parkway completely and restoring the riverfront as a park.

Everyone agreed that the Robert Moses Parkway was a planning error: it makes their city less appealing to tourists, and it lets those tourists drive through more quickly on their way to Canada.

In 2013, New York State finally saw the light and decided to remove two miles of the parkway completely.

Power Plants and Parkways on the Niagara

In 1887, Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux drew up the "General Plan For The Improvement of the Niagara Reservation." The greatest American landscape architect of the nineteenth century and the designer of New York’s Central Park, Olmsted drew up a plan meant to create a park that would let people view this scenic wonder – the world’s largest non-tropical waterfall – without damaging it.

But Niagara also had the potential to produce tremendous amounts of hydro-electrical power. In 1881, a small generator was built on the Niagara River, which ran local mills and lit up some local street lights. By 1896, enough electricity was being generated in Niagara that it began transmitting electricity to Buffalo, 26 miles away. More generating plants continued to be built through the first half of the twentieth century.

In 1956, Niagara’s largest hydroelectric plant was partially destroyed by a landslide, threatening tens of thousands of manufacturing jobs. In 1957, reacting to this crisis, Congress passed the Niagara Redevelopment Act, which gave the New York Power Authority a federal license to develop all of the Niagara River’s hydroelectric power that the United States was entitled to under a 1950 treaty with Canada.

The chairman of the New York Power Authority was Robert Moses. At the height of his power, Moses held twelve city and state positions, and his real focus was building highways and parks, rather than power plants. In addition to developing its hydroelectric power, he redesigned the Niagara River’s New York shoreline, by building two small parks to give people access to small stretches of river, and building a fenced-in parkway that cut off people’s access to the rest of the river.

The Robert Moses Parkway cut off pedestrian access to the Niagara Gorge

In 1961, on exactly the day that Robert Moses predicted, the Niagara project began producing power.

Building this power power project provided construction jobs and prosperity to Niagara Falls. The population rose to over 100,000 people and business boomed. But after construction was completed, the city entered a long period of decline. It lost almost half its people between the 1960 census and the 2000 census, when population was down to to 55,593. An urban renewal project of the 1960s and early 1970s made things worse by demolishing dozens of blocks and not building anything to replace most of them - leaving them as parking lots where no cars come to park. Then, in the late 1970s, an entire neighborhood was evacuated to escape the toxic pollution of the Love Canal.

Most everyone agrees that the Robert Moses Parkway hastened the decline of the city by drawing traffic away from Main Street, by speeding tourists through the city to Canada, and by cutting the city off from its most important scenic resource, the Niagara Gorge.

Removing the Robert Moses Parkway

In the year 2000, the Niagara Heritage Partnership called on the state to remove the 6.5-mile section of the Robert Moses Parkway between Niagara Falls, New York and Lewiston, New York, and to restore that portion of the Niagara Gorge’s shore with native vegetation. They said that parts of one lane of the parkway, furthest from the river, could be left as a bicycle path and hiking path, to allow people to enjoy the restored land. The proposal was quickly endorsed by the Sierra Club, the Audubon Society, and dozens of other groups.

The Heritage Partnership said this plan would both revitalize the city and create a nature reserve in the spirit of Olmsted’s original plan for Niagara falls.

The plan would also help the city’s businesses by routing traffic through the city that now bypassed it. The Heritage Partnership suggested that the traffic should be rerouted to streets adjacent to Main Street, bringing some cars to use the parking lots built as part of the urban renewal plan of the 1960s and early 1970s. To attract people, Main Street itself should be developed as a pedestrian-friendly street with sidewalk cafes, shops, restaurants and other businesses, complementing its existing assets, such as Earl Brydges Library, the Armory, and the Carnegie Building.

By restoring forests and grasslands, the plan would add 300 acres to the willdlife habitat along the Niagara River that the Audubon Society recently named an Important Bird Area because of its significance to migrating birds. This restoration would attract national and international attention, and it could make Niagara Falls a center of ecotourism.

The First Step to Improving Niagara Gorge

In 2001, just a year later, some aspects of the Heritage Partnership’s proposal were incorporated into a state plan to revitalize Niagara Falls.

Mayor Irene Elia, a Republican who took office in 2000, was close enough to New York’s Gov. George E. Pataki that he came to town after her victory and announced that the state would support a redevelopment effort. The state created USA Niagara Development Corporation as a branch of the Empire State Development Corporation, the state agency that helped make over Times Square during the 1990's.

As one of its initial improvements, the state converted five miles of the four-lane Robert Moses Parkway into a two lane road, reserving the other two lanes for pedestrians and bicyclists.

Beginning in September, 2001, the state implemented a pilot project that closed the two lanes of the parkway nearest to the gorge to traffic, so it can be used by bicyclists and hikers. The remaining two lane portion of the parkway was made two way, and its speed limit was lowered from 55 to 45 miles per hour.

In December, 2003, the state issued a report saying the pilot project was a success and should be made permanent. According to the report, accidents on this route had been reduced by 50% and emissions had been reduced by 16%. The report also mentioned increased access to the gorge under the new plan.

Community members demand total removal of the Moses Parkway

When the pilot project was proposed, The Niagara Heritage Partnership responded that it was seriously flawed, because tourists are unlikely to want to hike on concrete with two lanes of traffic nearby. The Niagara Heritage Partnership objected to the December, 2003 evaluation report, calling it an attempt to make the pilot alteration permanent rather than removing the road completely and restoring the area as a park.

In fact, the pilot project did little to link the waterfront with downtown, because people were still not able to walk across the remaining two-lane parkway. It is just one block from Main Street, but local streets still ended at a chain-link fence when they reached the parkway.

Removing the Rest of the Parkway

In February, 2013, New York State finally agreed to remove the Robert Moses Parkway entirely from Niagara Gorge. Commenting on the decisions, Niagara Falls Mayor, Paul Dyster, said, "I don’t think there’s anything that could be more impactful to the revitalization of downtown and the city’s North End business district than dealing with the Robert Moses Parkway."

The plan will retain the southernmost portion of the parkway, connecting Interstate 190 with Niagara Falls State Park.

It will remove the central part of the parkway, a two-mile stretch of the eighteen-mile parkway that goes through Niagara Gorge next to the city of Niagara Falls. The freeway will be replaced with a native plants and a multi-use trail for hikers, bicyclists, and horseback riders.

Vehicles will still have access to the gorge using an existing road, Whirlpool Street, which will be made into a low-speed two-lane road, like the road on the Canadian side of the gorge. This road will allow visitors to drive along the gorge and will provide a connection to parks further north, but it is further from the edge of the gorge and is a local road rather than a freeway.

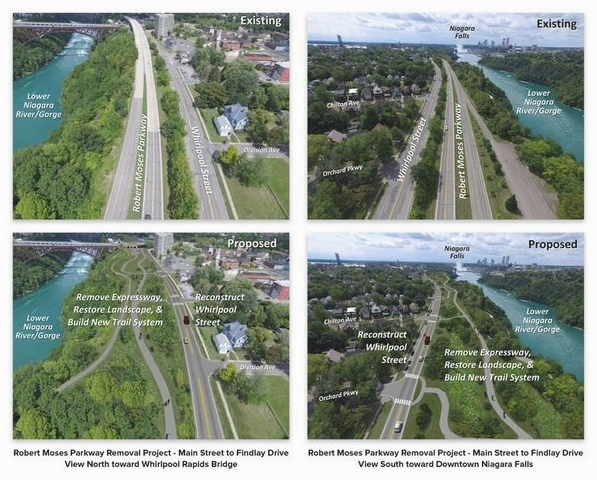

On March 22, 2016, Gov. Andrew Cuomo announced that the state would spend $42 million to implement the plan. The changes in the final plan are shown below. You can see that the freeway will be removed and replaced with landscaping and hiking trails, while Whirlpool Street will be reconstructed.

The final plan to remove the parkway

In these plans, you can see the pedestrian and vehicle connections with adjacent streets of Niagara Falls, which should help revitalize the city of Niagara Falls. The gorge will be accessible from the city again, for the first time since the freeway was built, more than a half century ago.

In a final coup de grace, the state voted on the same day to rename the remaining parts of the parkway as Niagara Scenic Parkway. In the fall of 2015, the Niagara County legislature passed a resolution calling on the state to change the name. In February 2016, Republican state senator Rob Ortt passed a bill to rename the parkway, and on Tuesday, March 22, the bill passed unanimously. Dennis Virtuoso, minority leader of the Niagara County legislature commented, "Tourists see the Robert Moses Parkway, they don’t know what that is, but if they see the Niagara Scenic Parkway, they’re more apt to take it for a scenic view."

A Milestone for Freeway Removal

It is remarkable that the state implemented the pilot project so quickly, despite its limitations, and it is remarkable that the state finally decided to remove the freeway.

This is a more radical freeway removal than the other American examples that we have looked at. Most of the others removed freeway spurs that were not completed, so removal did not have much effect on the freeway system as a whole. New York city removed a mainline freeway, the West Side Highway, only because it collapsed and was not rebuilt for decades because of political conflicts. But this project in Niagara Falls deliberately removed a mainline freeway, reducing freeway capacity in order to encourage people to stop in Niagara Falls, New York, rather than driving right through to Niagara Falls, Canada.

All the projects we have looked at are based on the insight that freeways blight the areas they go through. This one is also based on the insight that freeways simply encourage people to drive further – and that we may be better off removing a freeway so more people stop rather than driving through.

This is an idea that only radical environmentalists used to advocate, but now it has become mainstream. Even Gaming Magazine – a house organ of the gambling industry, which we would not expect to be aware of city planning issues – said in its article about revitalizing Niagara Falls that the Robert Moses Parkway is “widely held as a mistake in planning,” whose result is “simply directing people through the city and into Canada.”

Text copyright 2007, 2013 and 2016 by The Preservation Institute