Removing Freeways - Restoring Cities

Produced by the

Preservation Institute

Introduction:

Tear It Down!

by John Norquist

San Francisco, CA:

Embarcadero Freeway

San Francisco, CA:

Central Freeway

Milwaukee, WI:

Park East Freeway

Toronto, Ontario: Gardiner Expressway

New York, NY:

West Side Highway

Niagara Falls, NY:

Robert Moses Parkway

Paris, France:

Pompidou Expressway

Seoul, South Korea

Cheonggye Freeway

Freeway Removal

Plans and Proposals

Conclusion:

From Induced Demand

to Reduced Demand

by Charles Siegel

San Francisco, CA

Embarcadero Freeway

In 1986, San Francisco voters rejected the Board of Supervisors’ plan to tear down the Embarcadero Freeway, after a campaign where opponents said over and over that removing the freeway would cause gridlock.

At the time, it seemed that the vote on this initiative killed the proposal. People who hoped that San Francisco would follow Portland’s lead, starting a national movement to remove urban freeways, seemed to have lost.

Then, in 1989, the Loma Prieta earthquake damaged the Embarcadero Freeway and other freeways in the Bay Area - reopening the debate about whether the city should remove or repair this freeway.

This time, opponents could not use scare tactics about gridlock. The Embarcadero Freeway was closed after the earthquake, and there were some temporary traffic snarls, but by the time the city made the decision about the this freeway, traffic had adjusted to new conditions. There was no gridlock with the freeway closed, so opponents lost their strongest argument against removing it.

After the freeway was removed, in 1991, real estate values in adjacent neighborhoods went up by 300 percent. Entire new neighborhoods, oriented to the waterfront, were built and thrived in areas that had been hard to develop when the freeway stood as a wall that cut them off from the waterfront.

America’s First Freeway Revolt

California was a leader of the post-war freeway binge. Governor Earl Warren led the move to modernize the state by expanding the University of California, expanding the public school system, and expanding the freeway network.

During the post-war period, the California Division of Highways and the San Francisco Planning Department came up with a number of plans to crisscross San Francisco with freeways.

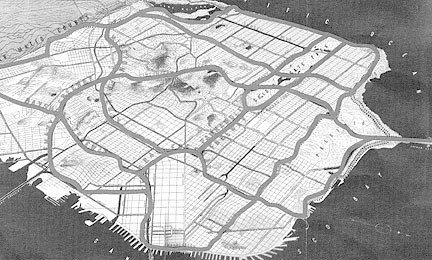

A 1948 plan to crisscross San Francisco with freeways

In 1951, the city adopted a freeway plan named the Trafficways Plan and began building. On October 1, 1953, the first three miles of the Bayshore Freeway opened, south of the Bay Bridge. The city’s freeway building was under way before the federal government passed the Interstate Highway Act in 1956

Two freeways on industrial land south of Market St. were built without much controversy: the Bayshore (101) and Southern (280), which are now San Francisco’s major freeways.

Then, in 1953, the city began building the Embarcadero freeway, which was meant to connect the Bay Bridge to Oakland with the Golden Gate Bridge to Marin County. At this point, as freeways extended north of Market St. into the city's downtown and neighborhoods, citizens began organizing against them.

On November, 2, 1956, the San Francisco Chronicle published a map of constructed and proposed freeways, with an editorial criticizing anti-freeway protesters for not acting “until the time was at hand for concrete pouring and when revision had become either impossible or extremely costly.”

Nevertheless, opposition continued to mount in the in the Sunset, Telegraph and Russian Hills, Potrero, Polk Gulch, Haight-Ashbury, and other neighborhoods that were in the way of freeway construction, setting off the most powerful neighborhood movement that the city had ever seen. In 1959, after neighborhood groups presented them with petitions signed by 30,000 people, the Board of Supervisors voted to cancel seven of the ten planned freeways in the city, including the Embarcadero freeway – the first time in history a government body voted to stop freeways.

The Embarcadero freeway had been completed as far as the Broadway off-ramp – 1.2 miles in all - and for decades, a small stub hung in the air beyond this off-ramp, showing that the freeway was meant to continue along the waterfront. The Broadway off-ramp funneled traffic to North Beach and Chinatown. During the 1960s, because of the traffic that this freeway brought in, Broadway in North Beach became the city’s major center of topless dancing and other “adult” entertainment.

This 1969 aerial photo shows that the Embarcadero Freeway went through the city

below Market St. and then continued up the Embarcadero to

the North Beach

off-ramp.

Notice the stub where it would have continued north along the Embarcadero.

Removing the Embarcadero Freeway

The battle to stop the Embarcadero Freeway gave great impetus to San Francisco's environmental movement, and environmentalists soon began to say that the city should correct its error by tearing down the part of the freeway that had already been built. By 1985, freeway removal was supported by a broad coalition of environmental groups, civic groups, and business groups who wanted to revitalize the waterfront.

In November, 1985, San Francisco’s Board of Supervisors - with strong leadership from Supervisor John Molinari and strong support from Mayor Dianne Feinstein and from Planning Director Dean Macris - voted to remove the Embarcadero Freeway and to replace it with a surface boulevard and an extension of the city’s trolley system. The project would cost $171 million, with San Francisco paying $10 million and the federal government paying the rest. Before it reached the full Board of Supervisors, the project had been studied in a 1000 page Environmental Impact Report and had been approved by the Public Utilities, Port, and Redevelopment Commissions and by subcommittees of the Board of Supervisors.

But Supervisor Richard Hongisto objected that the freeway removal “would be a deliberately designed traffic jam,” and he vowed to circulate an initiative to bring the issue before the voters.

Two measures appeared before the voters in the June, 1986, primary election. Hongisto’s initiative simply asked whether the freeway should be removed; Hongisto recommended a no vote, and the voters supported him by a margin of two to one. A compromise initiative supported by Mayor Feinstein asked whether the city should remove the freeway if studies showed that it would not cause traffic congestion, and voters also rejected this by a wide margin. Mayor Feinstein commented that this election would permanently “kill” the twenty-year campaign to tear down the freeway.

Even Herb Caen, beloved columnist for the San Francisco Chronicle, opposed the freeway removal. As it started going through commissions, Caen wrote. “Once again, there is ‘serious talk’ about tearing down the Embarcadero Freeway, an even worse idea than building it.” He continued to write against the freeway removal, and in his column of June 2, 1986, immediately before the election, he wrote, “It no longer blocks views, it provides some exciting ones. And while the drawings of a tree lined boulevard that would replace a torn-down freeway are alluring, so were the renderings of the New & Improved Market St. and look how that doggy-bow-wow turned out.”

It seemed that the movement to remove the freeway had failed, that the idea was dead. Then, on October 17, 1989, the 7.1 magnitude Loma Prieta earthquake caused sections of the Bay Bridge and of Oakland’s Cypress Freeway to collapse, and it damaged San Francisco’s Embarcadero and Central Freeways so severely that they had to be closed. The Embarcadero Freeway had been retrofitted for earthquake safety during the early 1980s, so it still stood, but it was so severely damaged that it could not be used.

After this freeway was closed, traffic was snarled temporarily, but drivers adjusted in a short time by using alternative routes and public transportation.

Before: The Embarcadero Freeway passed in front of the Ferry Building

Now the space in front of the Ferry Building accommodates

pedestrians and historic trolleys as well as cars.

Freeway opponents began a new push to remove the freeway rather than repairing it, and they succeeded now that freeway backers could no longer say that the traffic displaced from the freeway would create gridlock on local streets. Herb Caen changed his position and supported removing the freeway rather than repairing it. The main opponents were Chinatown merchants, who claimed that their business declined by 15 to 40 percent after the earthquake.

On April 16, 1990, the Board of Supervisors held a hearing on removing the Embarcadero freeway, and hundreds of Chinatown merchants closed their stores and went to the hearing to oppose the measure. Despite the opposition, Supervisors narrowly passed a resolution calling for a study of a surface boulevard and of the underground freeway along the Embarcadero proposed by Mayor Art Agnos. Because of the expense of building an underground freeway, Agnos shifted to backing a surface boulevard that just went underground in front of the Ferry Building at the foot of Market St. The city ultimately adopted the surface boulevard without any undergrounding.

February 27, 1991, Mayor Agnos struck the symbolic first blow to begin the demolition of the freeway. After leaving office, Agnos remarked that “The best decision I made as mayor was to demolish that freeway. It removed that scar and opened up one of the most important parts of this city for development.”

The San Francisco Chronicle commented on June 17, 2000, in a story about the ceremony dedicating the improved Embarcadero boulevard, that despite the fierce debates about the issue, “A decade later, it's hard to find anyone who thinks ripping down the freeway was a bad idea.”

Renaissance of the San Francisco Waterfront

Removing the double-decked Embarcadero Freeway opened the city to the waterfront.

The land that the freeway had occupied became available for new development and parkland:

- The land south of Market St. where the freeway looped through the city from the Bay Bridge to the Embarcadero was slated for 3,000 new housing units, 2 million square feet of offices and 375,000 square feet of retail. This loop had been called the “Terminal Separator,” because it was adjacent to the Transbay Bus terminal, and the profit from selling the land would be used to pay part of the cost of rebuilding this bus terminal as a multi-modal terminal for rail as well as for buses and light rail.

- The land immediately north of Market St. that was occupied by the freeway’s first off-ramp was used to improve a park. There was a proposal to build a Butterfly Discovery Museum there, but the city decided that it was more important to provide open space in one of the busiest parts of the city.

Before: The freeway's first off-ramp north of Market St.

Now the off-ramp no longer blights the park.

Note the thin point of the Transamerica Pyramid in the background in both pictures.

Most of the freeway was above the Embarcadero – a street rather than developable land – and the city spent $50 million to rebuild the Embarcadero as a boulevard flanked with palm trees, with a wide pedestrian promenade. In addition, by the late 1990s, began running historic trolleys on the Embarcadero between downtown San Francisco and Fisherman’s Wharf, using trolleys from the 1930s and earlier that were acquired from European and other American cities.

Replacing the double-decked freeway with a boulevard raised property values in the adjoining neighborhoods by 300 percent and stimulated development dramatically:

- Many individual developments were proposed and built. For example, the Ferry Building, which was once the city’s main ferry terminal but had been vacant for years, was redeveloped as a center for gourmet and natural food, the Gap built a new headquarters building, and Pier One was redeveloped as general office space.

- The Embarcadero Center, a multi-block retail and office center adjacent to the Embarcadero just north of Market St., bragged on its web site that “The Embarcadero Roadway Project has led to an entire renewal of the Downtown Waterfront District that is ensuring a bright future for Embarcadero Center.”

- Rincon Hill, adjacent to the Embarcadero just south of Market St., was developed as an entire new neighborhood. The city had been planning to redevelop this neighborhood with dense housing and shopping since the 1980s, but one developer commented that no one would build there in the 1980s: “Because it was then hemmed in on three sides by freeways, developers felt that Rincon Hill might not be the most inviting location for housing. ... The removal of the visual and physical barriers of a web-like freeway and the 12-acre Terminal Separator … dramatically showed the potential of Rincon Hill.”

- South Beach, south of Rincon Hill, was also developed as an entire new neighborhood, with housing, retail, and a new baseball field so close to the Bay that when a home run is hit over the right-field fence, the ball goes into the water. This neighborhood was not directly adjacent to the Embarcadero freeway – it was further south – but the opening of the waterfront to the north and the improvement of the Embarcadero as a boulevard extending in this direction helped it to thrive.

Apparently, the Chamber of Commerce was wrong during the 1950s and 1960s, when it constantly pushed for more freeway building, because it believed freeways would bring economic prosperity.

Herb Caen Way

In 1996, the city gave the name Herb Caen Way to the 25-foot-wide pedestrian promenade, running 3.2 miles along the waterfront next to the Embarcadero from South Beach to Fisherman’s Wharf.

On April 9, 1996, Caen had won a special Pulitzer Prize for his “extraordinary and continuing contribution as a voice and conscience of his city”; Caen’s columns had always been a combination of humor and nostalgia, and he said with characteristic modesty that he never wrote anything important enough to deserve a Pulitzer Prize.

Then, on May 30, 1996, Caen had announced in his column that he had cancer and would cut back on the number of columns he wrote, after producing at least 5 columns a week for over fifty years.

After he made this announcement, the Board of Supervisors, looking for a way to honor Caen before he died, decide to name this promenade Herb Caen Way.

Herb Caen Way with public art, a historic trolley, and a view of the Bay Bridge

On June 14, 1996, 75,000 people came to honor the columnist in a celebration at the foot of Market St., next to the Ferry Building. Caen died in 1997 at age 80.

No one seemed to remember that Caen had opposed removing the freeway during the 1980s - and that the place where they held the Herb Caen Day celebration would have been right under the freeway if this position had prevailed. Nevertheless, Caen spent much of his life walking the streets of San Francisco, so it is appropriate to honor him by giving his name to a promenade that was built when the city restored an important part of its pedestrian fabric.

Aerial photograph of the Embarcadero Freeway courtesy of Jeffrey Heller.

Two before photographs courtesy of Michael Kiesling.

Photographs of current conditions copyright 2007 by Charles Siegel.